by Sinan Adnan and Nichole Dicharry

Sunday, November 30, 2014

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

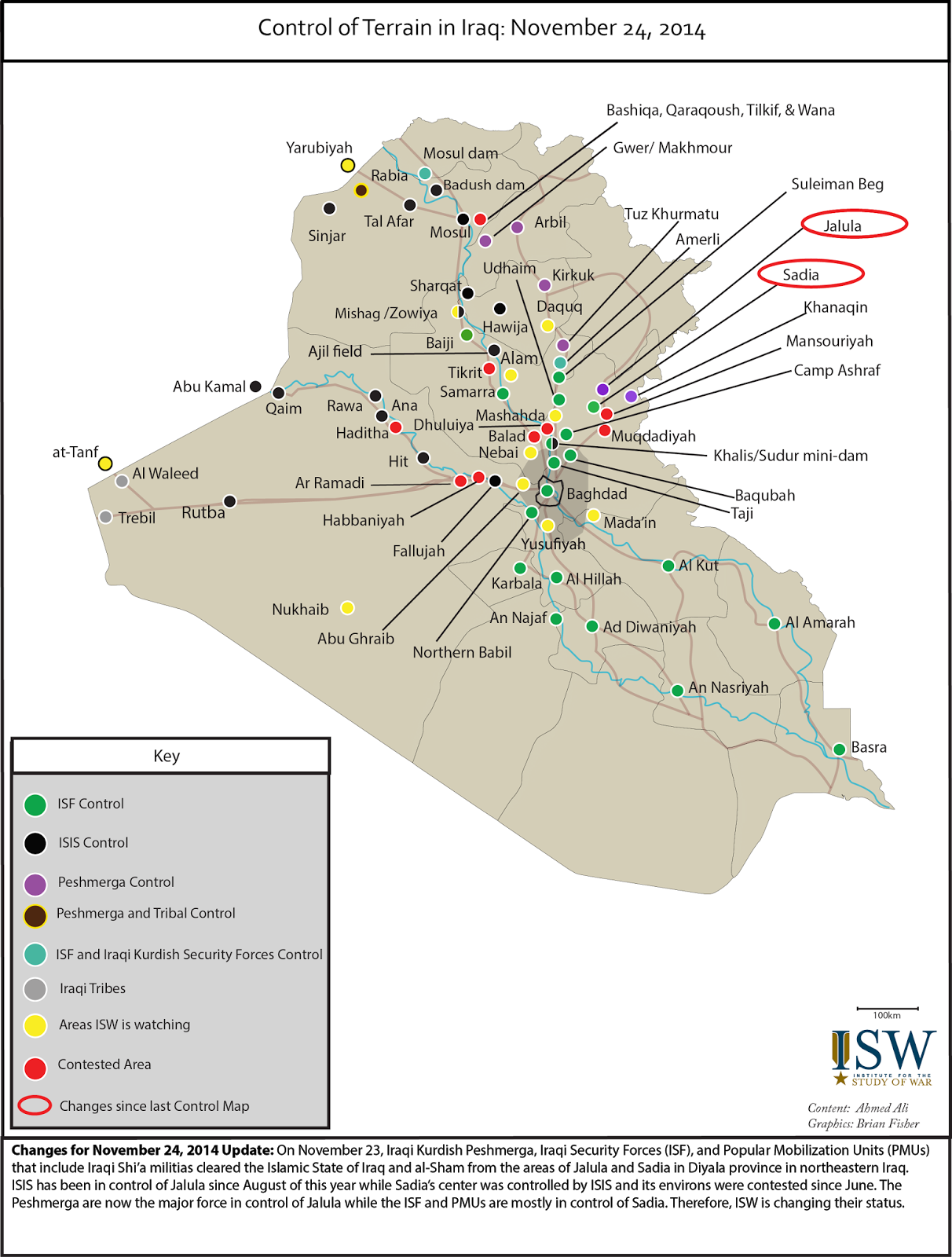

Monday, November 24, 2014

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Friday, November 21, 2014

Thursday, November 20, 2014

Control of Terrain in Iraq: November 20, 2014

by Ahmed Ali and Nichole Dicharry

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead.

ISIS Sanctuary Map: November 20, 2014

ISW has updated its ISIS Sanctuary map. This map, covering both Iraq and Syria, shows the extent of ISIS zones of control, attack, and support throughout both countries.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

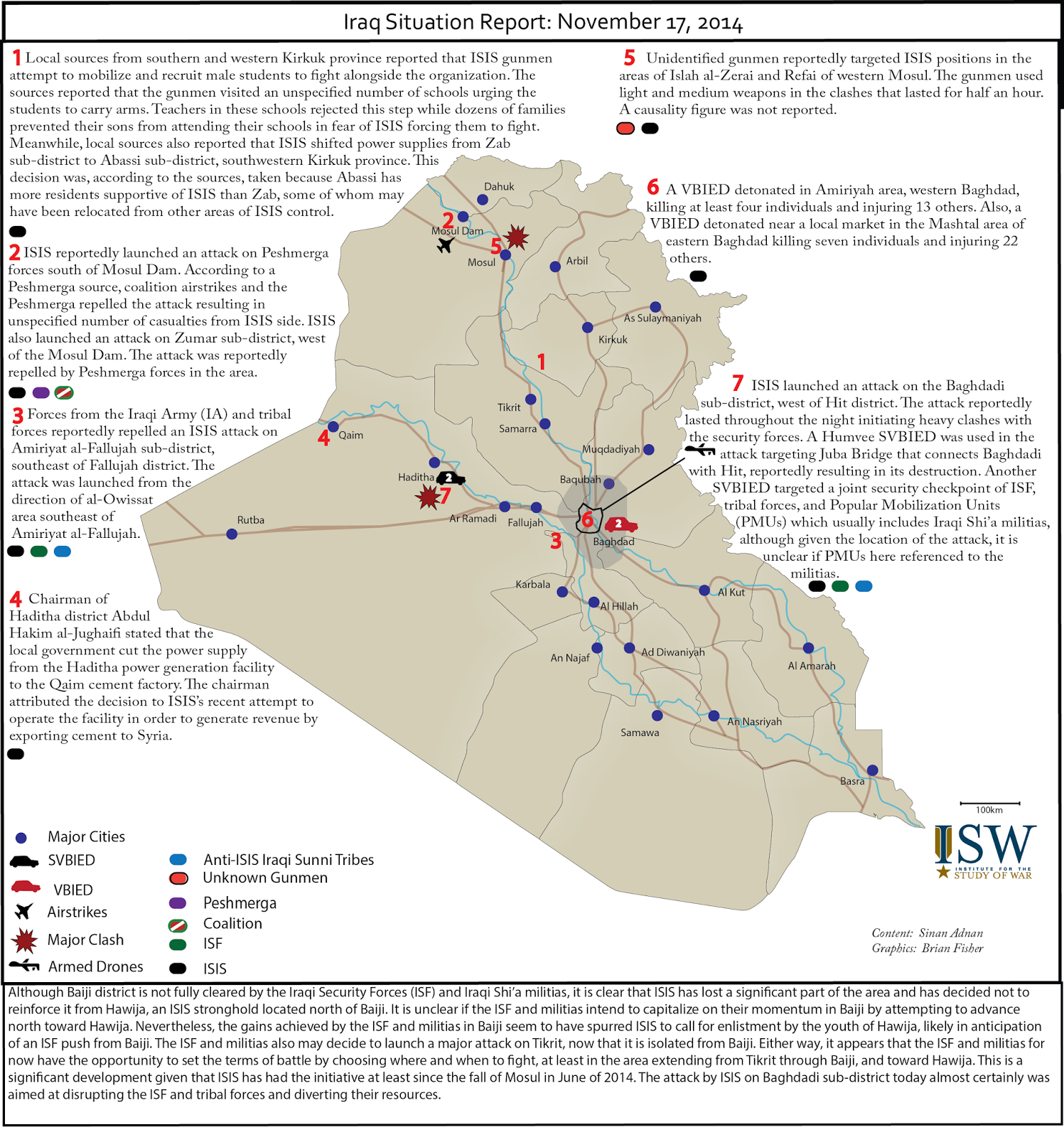

Monday, November 17, 2014

Sunday, November 16, 2014

Iraq Situation Report: November 14-16, 2014

by Ahmed Ali and Nichole Dicharry

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead.

Saturday, November 15, 2014

Peace-talks between the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria

By Jennifer Cafarella

Director of National Intelligence James Clapper is said to have told CBS's 60 Minutes that he has observed tactical cooperation between the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and Jabhat al-Nusra (JN). The two global, Salafi jihadist groups are engaged in an ideological struggle, or fitnah. They are competing for the leadership of the fight in Syria and recognition by the al-Qaeda movement, which has been conducting mediation attempts between the two since 2013 and in 2014 recognized JN as its official affiliate in Syria. Director Clapper's statements challenge recent public reports of their negotiations, which suggest that more fundamental mediation may be underway, indicating the possibility of heightened cooperation in coming months. The interview has not aired, and his statements may be more nuanced than the advanced press publicizing the show. But the issue at hand should not be whether more than tactical cooperation has already been observed, but rather, whether conditions are being set that will favor operational cooperation between ISIS and JN in the medium term. The mediation effort may not quickly result in Baghdadi and his inner circle reconciling with JN leader Abu Mohammed al-Joulani, but the groups are eventually likely to cooperate at the operational and strategic level, as they share mutual goals. In the short term, this may include joint action against the Assad regime, which could relieve pressure on ISIS from the regime in Deir ez-Zour and embolden JN to initiate offensive operations against the regime on battlefronts that have stalled. Furthermore, ISIS is under stress in Iraq, and may pursue the acquisition of manpower and other support from JN in Syria in order to reinforce and retake the offensive.

The publicly released information tells the story of hitherto unsuccessful attempts at cooperation at operational and strategic levels. According to a high-level Syrian opposition official and rebel commander cited by the AP, seven high-ranking members of JN and ISIS conducted a meeting in the town of Atareb, West of Aleppo city, on November 2 from midnight until 4:00 a.m. A “commander of brigades affiliated with the Western-backed Free Syrian Army” corroborated the report, adding that it was organized by a third party. According to the opposition official, the meeting included an IS representative, two emissaries from JN, and attendees from the Khorasan Group, who likely served as both the mediating force and organizing party. The AP also reported that Ahrar al-Sham and Jund al-Aqsa were present, however mistakenly characterized Jund al-Aqsa as a group that has pledged allegiance to ISIS.

Involvement of the Khorasan Group in ongoing attempts to mediate the fitna has also been reported by the Daily Beast, and, if true, likely indicates the veracity of reports of ongoing JN and ISIS negotiations. A number of Khorasan members initially entered Syria in the summer of 2013 as part of AQ’s “Victory Committee,” led by Khorasan member Sanafi al Nasr, that had been deployed by Zawahiri to mediate the growing schism between JN and ISIS. The involvement of these figures in current negotiations is therefore not a departure from past activities in Syria, and is likely a secondary line of effort complimenting the ongoing attempt to develop an attack against the West.

The Syrian opposition official cited by the AP also stated that JN and ISIS agreed to eliminate the moderate, Syrian Revolutionaries Front (SRF) at this meeting. This may have been a sensationalist claim attempting to inflate the threat to the moderate opposition in order to advocate for increased support from the west to the moderate Free Syrian Army (FSA)-linked rebels in Syria, under which the SRF falls. Since the initiation of U.S. – led airstrikes against both JN-linked “Khorasan Group” targets and ISIS in Syria, moderate rebels have accused the Obama administration of encouraging a future JN and ISIS partnership by giving them a common enemy. This is not an unfounded claim, as civilian discontent with the air campaign has fostered increased support for JN, whose rhetoric has shifted to condemn the air campaign in its entirety in a sign of rhetorical support to ISIS against the coalition. However, there is no indication that JN has yet shifted its disposition to the SRF in southern Syria, where JN and the SRF continue to cooperate in military action against the regime. While it is possible that a joint JN and ISIS force could escalate against Syria’s moderates in order to deter the development of an effective counter ISIS and counter JN ground force that is responsive to the West, this is not a likely short term course of action as it would risk provoking a considerable ramp-up in western military activity in Syria. Rather, joint action against the regime is the most likely avenue for cooperation between local JN and ISIS forces, possibly complimented by a continued campaign to subvert the influence of moderate rebels.

A second set of JN-ISIS negotiations appears to have been conducted, and reportedly involved a proposal to join forces against the regime rather than eliminating moderate rebels. On November 14, SOHR cited sources from Aleppo and ar-Raqqa that stated that JN, Jaysh al-Muhajireen wa al-Ansar (JMA) and “Islamic Battalions,” which typically refers to battalions from the Salafi Jihadist Islamic Front (IF), agreed to send the leader of JMA to Raqqa city to meet with the ISIS deputy of the “war minister” in an attempt to reach a cease fire that would allow for a joint focus against the regime while remaining in separate areas of operation. ISIS reportedly rejected this offer, demanding the ba’ya (fealty) of the JMA leader. According to Zaman al-Wasl, a statement by ISIS military commander Abu Omar al-Shishani corroborated this report, who stated that he had offered the terms of the truce to JN and the IF, who turned it down.

The use of the JMA leader as an emissary is an important indicator of the role Salafi Jihadist groups play in the ongoing fitna between JN and ISIS. Salafi Jihadist groups are a possible source of to JN and ISIS because their ideology and methodology makes them natural partners for both groups, and for that reason they often refuse to chose sides. These groups would likely serve as judges in a mediation if it occurred. They are therefore likely to advocate for, and possibly drive, a JN-ISIS partnering. Furthermore, in addition to the considerable participation of Jund al-Aqsa alongside JN in Jabal al-Zawiya, a local Salafist element from the Hama countryside with rumored ties to ISIS appears to have reinforced both groups in clashes against the SRF. On November 1, reports indicated that the Hama-based Salafist Uqab al-Islam Brigade seized a small town east of Ma’arat al-Nu’man from SRF forces. The brigade is reportedly a known ISIS affiliate in the area, and reports of its activity in Idlib during the ousting of the SRF indicates that it, or a similar brigade, may consist of ISIS reinforcements that reports claimed JN received in the area.

The official cited by the AP claimed that an ISIS deployment had been sent to Jabal al-Zawiya to support JN, and stated that during the alleged November 2 meeting, ISIS offered to send additional fighters to support JN in southern Idlib. According to the official, IS sent about 100 fighters in 22 pickup trucks to the Harakat Hazm stronghold of Khan al-Sunbul, but the reinforcements were not needed after Harakat Hazm withdrew after sixty five fighters defected to JN. The Daily Beast also reported this same number on November 11, but failed to quote any local sources and therefore may have simply recycled this report. However, local reporting also indicated that an ISIS convoy had been deployed to Jabal al-Zawiya, lending additional credibility. STEP News Agency that claimed an ISIS military convoy arrived in Idlib to support JN on October 28, and a November 1 report by the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) citing “trusted sources” that stated that ISIS fighters had reached the villages of al-Bara and Kensafara in order to support JN and Jund al-Aqsa against the SRF. ISIS is known to have presence in the eastern countryside of Homs and Hama provinces, and is likely engaged in an effort to acquire the allegiance of local ideologically aligned brigades in the area. JN is also known to have military presence in the Hama countryside, where it may be in regular local contact with ISIS or ISIS – affiliated forces.

Local and short-term cooperation between proximate JN and ISIS elements such as the reported deployment of ISIS, or ISIS-affiliated, forces to Jabal al-Zawiya may corroborate reports of ongoing JN and ISIS mediation efforts on a local level. Furthermore, the involvement of local Salafi Jihadist groups in both mediation and local coordination between JN and ISIS may indicate that such groups are well positioned to enact effective JN and ISIS collaboration on an operational level that is channeled through local affiliated groups without agreeing to an overt partnership between the groups. However, ISIS has interacted with proximate JN elements in the past despite the ongoing fitna, and local cooperation is therefore unlikely to be an indicator of high-level rapprochement between the two groups. For example, on August 24 ISIS reportedly withdrew from a base north of Hama city and turned it over to JN forces. JN and ISIS forces also continue to fight together against Hezbollah and the Lebanese Armed Forces in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, in addition to combating the regime in Qalamoun. It is presumably this sort of current tactical cooperation about which Director Clapper is speaking. This local cooperation preceded the emerging rumors of ISIS-JN negotiations, and therefore indicates that JN and ISIS may continue to cooperate tactically and to de-conflict their activities operationally even if no negotiated settlement between the groups' leaders is reached.

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Iraq’s Prime Minister Reshuffles the Security Commanders

By Ahmed Ali

Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi issued orders on November 12 to shuffle commanders and senior officials within the Iraqi security structure. This is his first major set of changes to the Iraqi Security Forces. Press reports indicate the changes focused on the Ministry of Defense and regional Operations Commands that were established by former Prime Minister and current Vice President, Nouri al-Maliki, although a full and official list of the changes has not been released. The Operations Commands function as centers in charge of providing and supervising security either for individual provinces or provinces grouped together based on geography. Based on the leaks, the changes have not included the other important security ministry, namely the Ministry of Interior, which in the Abadi government is under the control of the Iranian-backed Badr Organization. The changes are the most significant since Abadi became Prime Minister in September and represent the beginning of the Abadi era as Commander-in-Chief of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF).

According to Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi’s office, the personnel changes were intended “to consolidate the work of the military establishment based on professionalism and combating corruption in all its forms.” Abadi is highlighting counter-corruption because the Iraqi Security Forces and its commanders have a reputation for being corrupt, inefficient, and unprofessional. The changes included dismissing 26 commanders and the “retiring” of 10 other commanders. The prominent changes include:

- Replacing Iraqi Army Chief of Staff. General Babkar Zebari, an Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga Commander who has been in position since 2003, with Lieutenant General-Staff. Khurshid Salim Doski who is also an Iraqi Kurd and was the commander of the Ninewa-based 3rd Iraqi Army Division from 2006-2009. Doski was a deputy to Zebari before this change. Four of Zebari’s deputies who are unnamed were also dismissed.

- Dismissal of the Baghdad Operations Command (BOC) Commander, Lt. General-Staff. Abed al-Amir al-Shammari, who Vice President Nouri al-Maliki (during his prior premiership) appointed as the commander in May of 2013. It is unclear who will be the new BOC commander.

- Removal of the Mid-Euphrates Operations Commander, Lt. General-Staff Othman al-Ghanimi, from his position to be an assistant to Doski. Ghanimi was the commander of the 8th Iraqi Army division from 2005-2010. It is also unclear who will be the new commander of Mid-Euphrates Operations Command.

- Removal of the Anbar Operations Command (AOC) Commander, Lt. General Rashid Fleih, and reportedly moving him to be a deputy to Doski as well. Lt. General Qassim al-Mohammedi of the Anbar-based 7th Iraqi Army Division will reportedly take command of the 7th Division.

- Appointing Major General Imad al-Zuhairi to be the commander of the Samarra Operations Command instead of Sabah al-Fatlawi.

- Dismissal of the Ministry of Defense Chief of Military Intelligence, Hatem al-Magsusi. Magsusi was also appointed by Maliki in May 2013.

The dissolution of four Iraqi Army Divisions in the north as Mosul fell on June 10, 2014 dramatically changed Iraq’s armed forces, and the Iranian government has taken an increasingly direct role in the security sector. This shuffle is Abadi’s first major imprint on the security sector since becoming Prime Minister in September. His first significant administrative decision was dissolving the Office of the Commander in Chief (OCINC) shortly after assuming office by retiring Generals Abud Qanbar and Ground Forces Commander Ali Ghaidan. As premier Maliki had used OCINC to centralize the security decision-making under his sole authority without following the appointed, formal chain of command. Abadi’s intent to dissolve OCINC and the personnel shuffle illustrate his desire personally to affect Iraq’s reconstituting security services. Abadi is also clearly purging the security establishment of generals and commanders who were loyal to Maliki and can be described as “Maliki’s men.”

Within the new security structure, Abadi will also likely rely on Lt. General-Staff Othman al-Ghanimi as a major influencer within the Army Staff. Ghanimi was not perceived to be a close Maliki ally and this past makes him the type of commander that Abadi would likely need as he embarks on bringing Iraq’s security establishment under his influence. The removal of Hatem al-Magsusi is also significant given the intelligence deficit from which the ISF suffers.

It will also be important to watch who will be the new Baghdad Operations Command (BOC) Commander. Baghdad faces the continued threat of Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Devices (VBIED) and IEDs. These threats from the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) persist. In addition, the Iraqi Shi’a militias which operate in Baghdad with impunity and without regard to the ISF presence challenge the ISF in the capital. As a result, the next BOC commander will be crucial in either reigning in the militias or allowing their further freedom of movement.

Abadi’s changes are also intended to win public support. The public is indignant with the ISF’s performance . It is important for Abadi to signal to the public that he wants to combat corruption and remove incompetent commanders.

However, Prime Minister Abadi’s major challenge will be reforming and controlling the Ministry of Interior (MoI). MoI is currently led by Badr Member Mohammed al-Ghaban. The Iranian-backed Badr organization is not under Abadi’s command, but rather that competes with his formal authority as commander in chief. Former Transport Minister, Hadi al-Ameri, leads the Badr organization, which envisions itself as a chief player in a new Iraqi security structure. Furthermore, the militias that have gained acceptance and have been more effective than the ISF in countering ISIS formally fall under the control of the MoI as part of the Popular Mobilization Units (PMUs) directorate. Abadi may choose to confront the militias and challenge the MoI in the long-term, but in the short-term he will tolerate their preeminence as his government contemplates a strategy to defeat ISIS.

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead at Institute for the Study of War

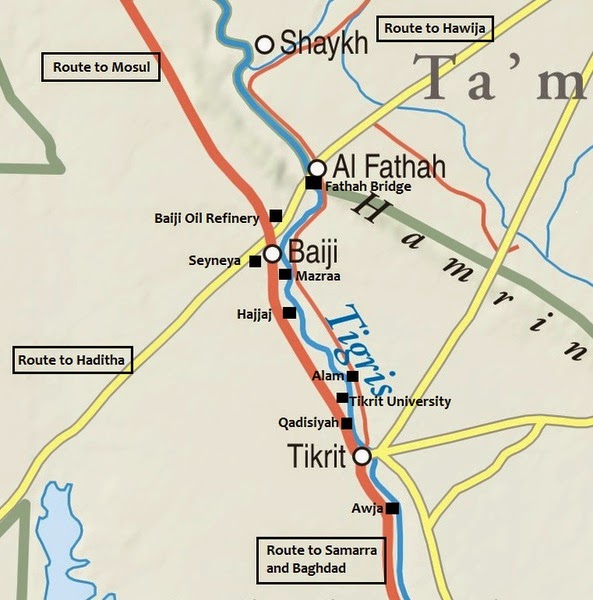

ISIS Risks Losing Baiji City

By Harleen Gambhir

Key Takeaway: The current Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) offensive in Baiji presents a critical opportunity for the ISF to open a gap in ISIS territory, and to set conditions for a future movement towards Mosul. Baiji is an operational node and likely proximate to an ISIS command and control center; its loss threatens a central corridor of the ISIS caliphate, and could facilitate isolation between ISIS’s military areas of operation within Iraq. In response to ISF pressure, ISIS has moved to reinvigorate control over Tikrit and Alam, east of Tikrit. If the ISF gain control of Baiji city and the Baiji-Haditha road, ISIS will likely move to secure supply lines to Syria in northwestern Iraq, and refocus on closing gaps on its Anbar front.

For the ISF

ISIS captured Baiji city on June 12, moving south from Mosul in its swift urban offensive. Since then, ISIS has both held Baiji city, and controlled the key Iraqi highway stretching south from Mosul to Tikrit. Denied access to this route, the ISF have been compelled to reinforce the ISF-held Baiji Oil Refinery, northwest of Baiji city, by air.

Though Iraqi Aviation launched airstrikes into Baiji multiple times over the past four months, no ground offensive was attempted until the ISF’s current effort. During the same time span, ISIS repeatedly initiated complex arms attack on the refinery, in order to control lucrative oil infrastructure and to close a gap behind the ISIS line from Mosul to Tikrit. As of November 3, the date of the most recent attempt, ISIS has not been able to control the refinery.

Through its current offensive, begun on October 24, the ISF aims to gain freedom of movement on the critical stretch of road from Tikrit to Baiji, and to take control of Baiji city itself. If successful, the operation will mark the first time that the ISF has retaken a major urban center from ISIS since the terrorist group’s June 2014 offensive. Control of Baiji city will also give the ISF a launching point to re-establish a ground supply route northwest of the city to the Baiji refinery. This route will allow the Iraqi Government to resume use of the oil facility, and establish a line of communication between two previously isolated ISF-held areas, Tikrit University and the Baiji refinery.

The loss of full control of Baiji is a significant blow to ISIS, and presents a key opportunity for the ISF. Baiji is a strategic crossroads that connects ISIS routes across the border to Syria, southwest to Anbar, south to Baghdad, and east to the Hamrin Ridge. Its environs are thus a likely area for ISIS strategic command and control. Since ISIS’s June 2014 offensive, the ISIS military stronghold in the historic Za’ab Triangle has provided forward protection to the ISIS political stronghold in Mosul. Equally as important, the Mosul-Tikrit highway has served as a central spine of the caliphate, from which ISIS has projected force to Mosul, Hawija, and Tikrit. The ISF and Shi’a militias have thus taken advantage of a critical ISIS vulnerability: peripheral control zones that, when opened, allow the ISF within striking distance of ISIS’s interior strongholds.

ISF’s Baiji offensive has opened a gap on the Mosul-Tikrit line, at the same time that ISIS efforts to close gaps on the Anbar front have stalled. It is possible that ISIS miscalculated its defensive requirements in central Iraq, committing forces to active fronts and leaving its core undermanned. As a result, ISIS may be facing the loss of key lines of communication among its Iraq efforts. The Baghdad Operations Command regained control of the Samarra-Ramadi road on October 28; the further loss of the Baiji-Haditha road would force ISIS to travel through Syria and down the Euphrates corridor in order to communicate and supply across the central Iraq and Anbar systems. This task will be increasingly difficult, as U.S. and coalition forces follow through on a stated intention to separate ISIS’s Iraq and Syria forces.

The ISF push for Baiji began with movement from north of Tikrit, led by the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Services (CTS). From October 24 to October 27, the ISF’s Golden Division cleared the Hajjaj village, north of Tikrit. U.S. and coalition partners provided air support throughout the operation. At the start of the ISF’s activities in Hajjaj, on October 24, five coalition strikes targeted an ISIS training camp and ISIS vehicle south of Baij city. Iraqi news sources reported that the strikes killed militants who were planting IEDs in the Mazraa area, north of Hajjaj on the road to Baiji.

After clearing Hajjaj on October 27, the Golden Division moved north, reportedly slowed by roadside IEDs. U.S. aircraft accompanied this movement, targeting ISIS north of the city, south of the Baiji Refinery. On October 30, ISF took control of Mazraa and the Sinai area southwest of Baiji. The same day, U.S. and coalition partners targeted an ISIS unit near Baiji. Anonymous Iraqi Police sources claimed that airstrikes on that day destroyed 37 vehicles that were headed to clash with the ISF. If true, the report would either indicate that coalition and Iraqi Aviation were coordinating strikes in support of ISF movement, or that the coalition was able to target a particularly large gathering of forces.

By the end of October 30, Iraqi Army reinforcement had arrived at the outskirts of Baiji, positioning tanks at city entrances to shell ISIS positions within the city. Local sources reported that 150 Baiji youth had joined the security forces by that day as well.

In response, ISIS took defensive measures on October 30. ISIS detonated a Suicide Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Device (SVBIED) targeting a security patrol on the road from Mazraa to Baiji. In an attempt to subdue Baiji’s tribal population, ISIS fighters used IEDs to destroy the home of Ghalib Nafous al-Hamad, a sheikh of the Jisat tribe, in central Baiji. ISIS also reportedly executed 17 other members of the Jisat tribe.

Despite these efforts, on October 31 a joint ISF and Shi’a militia force launched an assault on Baiji proper, making gains in the western, southern, and eastern parts of the city. On the same day, Baiji’s Iraqi Police opened a new office in al-Hajjaj, rallying security forces that had previously reported to the police office inside the city. The IP called for Baiji policemen and tribal elements to hold the territory south of Baiji so that security forces could advance further. Over the course of October 30 and 31, U.S. and coalition partners targeted an ISIS unit near Baiji, and a large ISIS unit north of Tikrit. By November 1, ISF had reportedly seized the main road in the city. Reinforcements began to clear Baiji and the Seneya area to the north, starting to dismantle IEDs on the road leading to the Baiji Oil Refinery.

In response, on November 4, ISIS began a campaign of mass arrests in Baiji, forcing youth to fight alongside ISIS, and to act as human shields for ISIS fighters moving heavy weapons from the city’s center to its outskirts. Dozens of families reportedly fled from Baiji and Seneya, towards the Abbas and Zab sub-districts of Hawija. On November 5, ISIS further encouraged this flight by detonating IEDs in 20 houses belonging to tribal sheikhs and ISF personnel in Baiji. ISIS also executed seven members of the same family in the Shawish district of Baiji on November 6.

As of November 12, ISIS retains a presence in the city, but has not been able to mount a successful counterattack. The ISF repelled an ISIS attack on Mazraa on November 1, and another attack on the Baiji Oil Refinery on November 3. U.S. and coalition forces conducted airstrikes against ISIS positions outside of the city on November 3, while IA Aviation bombed ISIS positions within the city on November 4. The air campaign continued on November 6, with IA artillery and IA Aviation shelling ISIS positions. ISF also attacked ISIS on the ground, making gains in the al-Buayji sub-district of Baiji on November 6, and destroying ISIS SVBIEDs on November 7.

In the next few days, between November 7 and 10, U.S. and coalition partners conducted 7 airstrikes near Baiji. Also on November 10, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) used Reaper remotely piloted air systems (RPAS) north of Baiji to target ISIS members planting IEDs. By November 10, ISF had captured the police directorate within Baiji, and were stationed 3 kilometers from the Baiji refinery. On November 11 the ISF cleared central Baiji, taking control of the Fatah mosque and the municipality building, where Baiji mayor Mahmoud al-Juburi reportedly resumed his duties.

Some ISIS elements remain in the city, as demonstrated by an ISIS suicide attack on November 11. Coalition airstrikes are ongoing near Baiji, with 5 strikes reported between November 10 and 12. Yet there are signs that ISIS is retreating: on November 12, an anonymous security source in Salah ad-Din reported that ISIS forces “almost completely” withdrew from Baiji using the Fatah bridge, likely heading southeast to Alam.

In response to the ISF offensive, ISIS’s defensive objectives are to prevent ISF from gaining freedom of movement on Mosul-Tikrit road, and to ensure adequate redundancy in ISIS interior lines used to move fighters and resources between Mosul and Anbar. ISIS’s offensive objectives are to continue its Anbar and Baghdad efforts, but now with a newly urgent need to disperse the ISF so that they do not mass at a point of ISIS weakness.

In the days following ISF movement into Baiji city, ISIS undertook defensive measures south and southeast of Baiji to prevent further ISF encroachment into ISIS areas of control. These ISIS attacks were directed both at security forces directly on the Baiji-Tikrit highway, and at local and tribal leaders in nearby urban areas, particularly in ISIS-held Tikrit and Alam. On November 1, ISIS forces, including suicide bombers, attacked ISF positions at Tikrit University, north of Tikrit. The next day, on November 2, ISIS detonated explosives inside of 7 homes in Alam, including the houses of the chairman of the regional sheikh council, the chairman of the regional security committee, and a regional TV channel director. ISIS detonated another bomb inside a house south of Tikrit on November 3, during the course of ISF and Popular Mobilization (units that include Shi’a militias) operations in the area. On November 5, ISIS further emplaced IEDs on the homes of 50 ISF personnel in the Qadisiyah neighborhood, north of Tikrit. This was followed on November 7 by a “massive” SVBIED attack launched against IA and Popular Mobilization units in Awja, south of Tikrit. Attacks on security patrols, offensive IEDs, and an escalation in the significance of targets are all signature signs of ISIS disruption, recalling al-Qaeda in Iraq’s (AQI) historic response to pressure from U.S. forces in 2007 and 2008.

In this current period of urban control, ISIS disruption is also evident from widespread retaliatory attacks against civilian residents of occupied areas. Two days after the ISF began its assault on Baiji proper, on November 2, unidentified gunmen reportedly distributed leaflets in Alam, near a square where the ISIS flag was reportedly burned and replaced with the Iraqi flag. The group claimed responsibility for the flag burning and the killing of ISIS members, and also called for residents to fight ISIS. ISIS responded harshly, destroying homes as described above and arresting 70 individuals, mostly of the Jubur tribe.

ISIS’s need to secure Alam was made more urgent by ISF pressure from the west at Baiji and Tikrit, and from the east at Tuz Khurmatu and Suleiman Beg. On November 9, ISIS used loudspeakers in Alam to warn members of the Jubur tribe that they had four hours to vacate the area or be killed. The next day, on November 10, mortar rounds reportedly landed on an ISIS gathering in Alam. ISIS consequently arrested 3 individuals in the area. On November 11, ISIS deployed 15 SUVs loaded with weapons to the area.

It is likely that ISIS forces that withdrew from Baiji on November 12 redirected southeast in order to secure Alam. Anonymous security sources reported that after withdrawing from Baiji ISIS deployed 400 fighters in 100 cars throughout Alam on November 12, placing VBIEDs and members wearing SVESTs in agricultural areas in the city. ISIS also abducted 50 individuals from the Jumaila village in Alam, and detonated IEDs to demolish the house of a cleric known for his anti-ISIS stance, Abu Manar al-Alami. As a result of ISIS operations, 80% of Alam residents have reportedly fled towards Kirkuk, Balad, and Samarra.

ISIS’ defensive operations have possibly also extended northeast of Baiji. On October 30, as ISF forces approached Baiji proper, ISIS forces detonated explosives on the railroad tracks running alongside the Fathah Bridge, which connects Baiji to Hawija. ISIS also emplaced IEDs on the bridge, ensuring the ability to destroy the bridge if needed to impede ISF movement. The next bridge crossing the Tigris to the north is near Mount Makhoul, where on November 10 the Iraqi Ministry of Defense announced that Iraqi fighter jets killed 40 ISIS militants. ISIS appears to be expecting an ISF advance into southwest Kirkuk. On November 11, an anonymous security source reported that ISIS initiated a conscription program in Hawija district and Riyadh, Zab, Abbasi, and Sharrad sub-districts, ordering each household to nominate a young man who would fight when ISF forces reached the area.

Offensively, ISIS will likely continue its Anbar efforts, with a strengthened requirement to disperse ISF manpower, and to close gaps between its areas of control in the region. ISF forces have been in a weakened position in Anbar, while ISIS’s proximity to Baghdad from the west and increased killing of Iraqi tribesmen has attracted the ISF’s attention. With a recent defeat at Jurf al-Sakhar, a likely withdrawal from Baiji, and a stalled offensive at Ayn al-Arab/Kobane in Syria, ISIS will likely its direct efforts towards Anbar.

It would be reasonable to expect ISIS to undertake renewed offensives at Haditha or Amiriyat al-Fallujah, current gaps in ISIS’s Anbar line of control. However, ISIS will have to weigh its gap-closing objectives with ongoing ISF counteroffensives, especially around ISIS-controlled Hit. This concern is heightened by the increased involvement of U.S. forces in Anbar, namely the arrival of 50 U.S. Marines at Asad Air Base, west of Hit, to train 400 tribal fighters.

In order to politically divert the ISF, ISIS will likely continue, and possibly ramp up, its efforts to stoke sectarian tensions. Mass executions of the Sunni Albu Nimr tribe are ongoing in Anbar. This targeting of tribal Sunni populations has been paired with a series of VBIEDs and SVBIEDs in Baghdad, most targeting Shia ‘Ashura gatherings and security checkpoints. Between November 1-3, 3 SVBIEDs and 3 VBIEDs detonated across Baghdad. On November 4, ISIS also detonated an IED in Latafiyah, southwest of Baghdad, targeting civilians returning from an Ashura pilgrimage to Karbala. While these explosive attacks in Baghdad are to be expected, especially during Shi’a holy days, it is prudent to watch for additional signs of ISIS attempting to divert tribal and Shi’a militia support away from a Za’ab-centric effort.

If the ISF gains control over the Baiji-Haditha road, then ISIS will likely give renewed attention to the Syrian supply corridor through northwestern Iraq. The stretch of the Jazeera desert from Raqqa to Mosul is vital connective tissue between ISIS political centers of gravity. Without access to the Samarra-Ramadi or Baiji-Haditha roads, the territory may also become a necessary supply route between northern Iraq and the Euphrates corridor. ISIS will likely pressure Kurdish forces in northwestern Iraq to ensure freedom of movement in this corridor.

Control of Baiji would provide the ISF with the unprecedented opportunity weaken ISIS at a place of core military strength. A strategy to inflict the most damage to ISIS should set conditions for a maneuver assault on Mosul. This involves both pushing north to Hawija, Qayarah, and Sharqat, and also swinging west to Tal Afar. When Iraqi Security Forces begin operations to clear Mosul in the spring of 2015, they will thus be positioned to approach from the west and the south, isolating the city from possible avenues of ISIS reinforcement.

The ISF should exploit Baiji’s position as a central point in ISIS’s Iraq theater. Denying ISIS access to routes in central Iraq would cut the connection between ISIS forces in Anbar and the Za’ab, and would isolate ISIS forces between Tikrit and Samarra. Severing these links between forces would limit ISIS’s ability to coordinate efforts across fronts. Consolidating control in Baiji and the surrounding routes and moving outwards would set conditions for an eventual ISF offensive on Mosul.

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

Monday, November 10, 2014

Iraq Situation Report: November 10, 2014

by Ahmed Ali, Sinan Adnan, and Brian Fisher

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead.

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Iraq Situation Report: November 8-9, 2014

by Ahmed Ali and Nichole Dicharry

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead.

Control of Terrain in Iraq: November 9, 2014

by Ahmed Ali and Nichole Dicharry

Ahmed Ali is a Senior Iraq Research Analyst and the Iraq Team Lead.

Friday, November 7, 2014

Wednesday, November 5, 2014

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

Monday, November 3, 2014

Sunday, November 2, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)